Paskal Zhelev

University of National and World Economy

Bratislava University of Economics and Business

Monika Moraliyska,

Ivet Tileva

University of National and World Economy

https://doi.org/10.53656/his2025-6s-4-glo

Abstract. This article examines the European Union’s trajectory as a pillar of globalization in historical perspective, focusing on the interplay between structural openness and uneven development since 1970. Globalization has advanced in cyclical waves marked by episodes of slowdown and retrenchment, yet the EU has consistently maintained an outward orientation. Using trade as a share of GDP as the primary indicator, the paper traces long-term trends in European openness and highlights three critical inflection points: the stagflation era of the 1970s – 1980s, the global financial and eurozone crises of 2008–2013, and the pandemic-driven polycrisis of 2020 – 2024. Institutional analysis shows that each disruption was met with innovations–from the Single European Act and the euro to the European Stability Mechanism and NextGenerationEU – that reinforced openness. At the same time, the benefits of integration have been unevenly distributed: peripheral economies in Southern and Eastern Europe bore disproportionate adjustment costs unless compensated by supranational instruments. The EU’s historical experience thus illustrates both the resilience of globalization through regional integration and the enduring challenge of asymmetry within it.

Keywords: European Union; Globalization; Deglobalization; Regional integration; Trade openness; Core-periphery asymmetries; Uneven development

- Introduction

Globalization has been the dominant paradigm in international political economy for decades, yet its durability has repeatedly been questioned during episodes of disruption. Recent crises – from the global financial meltdown to the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine – have revived debates about fragmentation and retreat. Some analysts argue that globalization remains surprisingly resilient despite geopolitical turbulence (Setser 2024), while others emphasize that integration today is shaped less by universal liberalization than by shifting regional dynamics (O’Neil 2022).

The rise of regionalism is central to these debates. Far from being an alternative to globalization, regional blocs often act as its carriers, sustaining openness even when global flows slow. Scholars have therefore described regional integration as “globalization by other means” (Barbieri 2019). The European Union (EU) exemplifies this dynamic: it has combined internal market deepening with external trade policy, embedding its project within the multilateral system while projecting economic influence worldwide.

Yet the trajectory has never been even. Structural asymmetries between Europe’s core and periphery mean that integration has often benefited larger, more diversified economies more than smaller or vulnerable ones. Recent work underlines how crises – such as the eurozone debt crisis or the Ukraine war – have widened gaps in resilience between regions (Celi et al. 2022). This echoes long-standing concerns that globalization, while persistent, generates distributive tensions that can undermine its legitimacy (Rodrik 2011).

Against this backdrop, the present article argues that the EU has functioned as a structural pillar of globalization since the 1970s, consistently maintaining openness even in periods of global contraction. The analysis combines quantitative evidence on trade openness with qualitative examination of institutional evolution and comparative case studies of peripheral economies. Three critical episodes – 1973 – 1985, 2008 – 2013, and 2020 – 2024 – are examined as turning points that tested the resilience of openness and exposed its uneven effects.

The significance of this historical perspective extends beyond academia. By examining how the EU continually recommitted to openness through successive crises, this study offers insight into contemporary policy debates. Today EU leaders grapple with questions of how to remain open to global trade while guarding against external shocks – a balance now encapsulated in the idea of “open strategic autonomy” (Miro 2022). Situating the EU as a pillar of globalization is thus not only a historical inquiry but also a lens to understand the EU’s current strategy for navigating a fragmenting world. This framing bridges the past and the present, making the analysis especially pertinent to EU studies scholars and policymakers.

To frame the analysis that follows, it is useful to outline the methodological orientation of this study. The article adopts a descriptive historical lens informed by economic history and international political economy. This perspective enables the integration of long-run quantitative evidence with established secondary scholarship, facilitating a systematic tracing of major turning points and institutional developments within the EU over time.

- Globalization and Deglobalization: Concepts and Periodization (1970 – 2024)

Understanding the European Union as a pillar of globalization requires situating its trajectory within the broader cycles of global integration and retreat. Since the 1970s, globalization has not followed a linear path but has advanced through alternating phases of expansion, slowdown, and crisis-induced contraction. Distinguishing between globalization, deglobalization, slowbalization, and emerging patterns of polyglobalization provides the conceptual foundation for analyzing how successive shocks – from oil crises to financial turmoil and the recent polycrisis – tested Europe’s openness. These categories illuminate how the EU remained structurally globalized even when world trade and investment faltered, and why its integration project must be seen as resilient rather than fragile.

Globalization is a multidimensional process of intensifying cross-border flows of goods, services, capital, people, and ideas, supported by liberalization, political frameworks, and technological progress (Stiglitz 2002). Yet its trajectory is cyclical rather than linear. Periods of expansion have been punctuated by contractions, often triggered by global crises. To capture these dynamics, scholars distinguish between several related concepts.

Globalization refers to the sustained intensification of international integration, driven by liberalization and technological change. Deglobalization describes a prolonged contraction, often crisis-induced, in which states retrench and global flows decline; it does not signify the end of interconnectedness but rather its reconfiguration (Rodrik 2011). Slowbalization captures a middle ground: integration continues but at a slower pace, reflecting structural limits and geopolitical tensions (Loots 2024). More recently, scholars have advanced the notion of polyglobalization, where globalization persists in fragmented and multipolar forms, shaped by regionalization, digitalization, and competing power centers (Mittelman 2023).

These distinctions provide a useful lens for interpreting the European Union’s trajectory since the 1970s (Table 1). Over this period, the EU has been exposed to successive waves of disruption that tested the durability of its openness but did not dismantle it.

The first major disruption was the oil shocks of the 1970s. The Yom Kippur War (1973) and the Iranian Revolution (1979) caused oil prices to surge from $3 to $12 and later nearly $39 per barrel (Yergin 1991; Hamilton 2004). Western Europe was hit by stagflation, rising unemployment, and energy insecurity (Stern 1986). While trade growth slowed markedly, integration remained resilient. The turbulence of this period thus marked Europe’s first encounter with deglobalization pressures, but it also reinforced the need for closer economic coordination.

Table 1. Chronological synthesis of major episodes of globalization slowdown relevant to the EU (1973 – 2024)

| Period | Trigger(s) | Main EU Impact | Phase |

| 1973 – 1985 | Oil shocks, stagflation | Inflation, stagnation, reduced trade growth | Slowdown / early deglobalization pressures |

| 2008 – 2013 | Global financial & eurozone crises | Sharp contraction of trade and investment flows | Slowbalization / temporary contraction |

| 2020 – 2024 | Brexit, COVID-19, Ukraine war | Abrupt collapse in mobility, supply chain disruption | Polycrisis / polyglobalization |

Source: Authors

The second turning point was the global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent turmoil in the eurozone. The collapse of financial markets spilled over into trade and investment flows, and economic integration slowed significantly. While some observers framed this as a retreat, it is better described as slowbalization – a temporary contraction in which globalization lost momentum but did not reverse (European Commission 2010; James 2014).

The third wave of disruption began in the 2020s. Brexit represented a direct form of disintegration, while the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly curtailed international mobility and disrupted global supply chains (Queiroz et al. 2022). These pressures were compounded by geopolitical shocks such as the war in Ukraine. Rather than straightforward deglobalization, this period reflects a broader polycrisis that reshaped rather than dismantled integration. The EU’s openness increasingly operated in a context of polyglobalization – fragmented, regionalized, and digitalized, but still structurally global (Wolf еt аl. 2021).

Taken together, these episodes demonstrate that globalization in Europe advanced not along a straight line but through cycles of disruption and renewal. Each crisis generated severe pressures and interruptions, yet the overall trajectory remained one of openness, albeit transformed in scope and character.

- Long-Term Trends in EU Trade Openness (1970 – 2024)

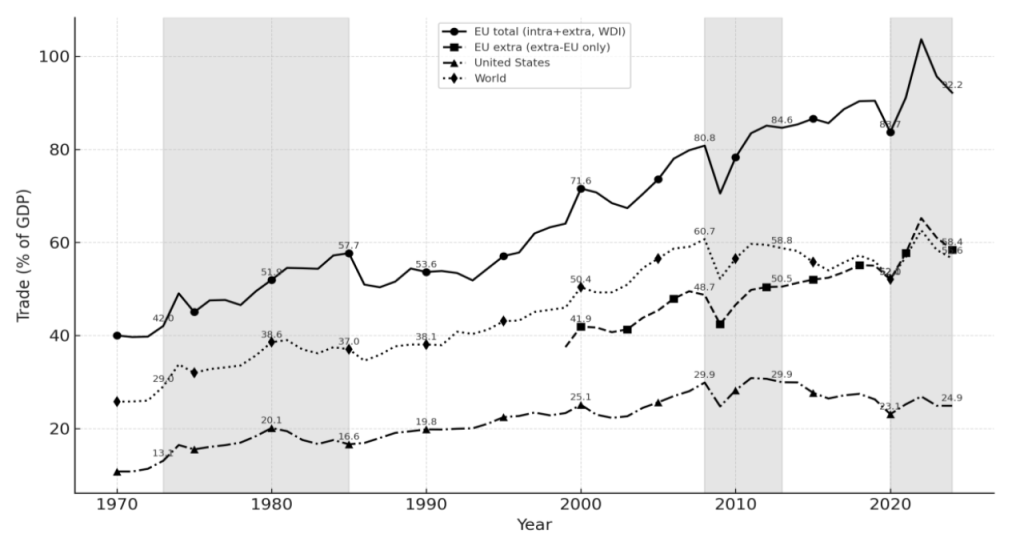

Using World Bank data on trade (exports + imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP), we can trace the European Union’s trade openness over the past half-century. Figure 1 plots this trajectory alongside the world average and the United States. The overall pattern is unambiguous: the EU has become markedly more open, with trade/GDP rising from around 40% in 1970 to above 90% in 2024, after peaking at 103.6% in 2022. By contrast, the world average increased from 25.8% in 1970 to 56.6% in 2024, while the United States remained far lower, moving from 10.8% to 24.9%. The EU’s trajectory thus reveals not only participation in global integration but also a degree of openness well beyond that of other major economies.

A closer look at benchmark years illustrates this divergence. In 1973, EU trade reached 42.0% of GDP, compared with 29.0% worldwide and 13.1% in the U.S. By 2000, EU openness had risen to 71.6%, while the world stood at 50.4% and the U.S. at 25.1%. Even after the global financial crisis, when EU trade/GDP dropped to 70.5% in 2009, the Union recovered to 84.6% by 2013, whereas the world averaged 58.8% and the United States 29.9%. The COVID-19 shock produced another temporary decline, with EU openness at 83.7% in 2020, but by 2022 the ratio had surpassed 100% for the first time in history.

Figure 1. Trade Openness of the EU (total and extra-EU), the USA and the world (1970 – 2024, trade as % of GDP)

Source: Authors, based on World Bank, World Development Indicators; Eurostat, national accounts.

These figures, however, reflect intra-EU as well as extra-EU flows, and thus capture the deepening of the internal market as much as the Union’s external integration. When intra-EU trade is excluded, the pattern remains one of structural openness, though at lower levels. The external-only ratio (extra-EU exports and imports relative to GDP) was 37.5% in 1999, 65.2% in 2022, and 58.4% in 2024. Even on this narrower measure, the EU consistently outpaced the United States and, from the 2020s onward, matched or exceeded the world average.

Taken together, the evidence underscores two points. First, crises punctuated but did not derail the long-term rise of European openness. The oil shocks (1973 – 1985), the global financial and eurozone crises (2008 – 2013), and the COVID-19 polycrisis (2020 – 2024) produced marked but temporary contractions. Second, whether measured as total or external-only trade, the EU emerged as the most open major economic bloc, highlighting the extent to which globalization has been embedded in the logic of European integration.

- Institutional Evolution and Anti-Crisis Responses of the EU

Across five decades, European integration advanced not by insulating the Union from shocks but by converting them into institutional upgrades that preserved openness. The pattern is cumulative: crises expose coordination gaps; ensuing reforms expand the EU’s capacity to sustain the single market and an outward orientation.

4.1. 1970 – 1992: From Customs Union to Internal Market under Energy Stress

The customs union created in 1968 – internal liberalization backed by a standard external tariff – anchored a model of “open” integration that could absorb external shocks while avoiding beggar-thy-neighbour responses (Ovádek & Willemyns 2019). The 1973 – 74 oil shock was the first major test. Divergent preferences, notably between France and Germany, revealed how asymmetric energy dependencies and limited supranational authority constrained collective action; yet member states did not revert to national protectionism. Instead, exchange-rate coordination via the European Monetary System (1979) and the Single European Act (1986) pushed market-making forward. This “neglected integration crisis” prefigured later energy episodes: structural asymmetries complicated coordination but did not derail the move to a deeper internal market (Schramm 2024).

4.2. 1992 – 2007: Maastricht, the Euro, and the External Projection of Rules

With the internal market taking shape, Maastricht (1992) deepened supranational competences in EMU and trade, consolidating the Common Commercial Policy as Europe’s external economic lever. Progress was uneven and often conflict-ridden, but trade policy frequently advanced by “failing forward”: competence disputes and political blockages produced legal-institutional innovations (including through the ECJ) that enlarged EU capacity (Freudlsperger 2021). WTO membership (1995) embedded regional openness in multilateral rules, while the 2004/2007 enlargements exported the acquis to the East – external Europeanization that widened the reach of single-market regulation (Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier 2005). The euro (1999/2002) reduced currency risk and anchored financial integration, consolidating the Union’s position as a pro-globalization pole.

4.3. 2008 – 2013: From Ad-Hoc Rescue to Banking Union

The global financial crisis and euro-area turmoil made EMU’s design gaps explicit: national monetary/exchange-rate tools had been ceded without adequate common risk-sharing (Lane 2012; De Grauwe 2013). The EU layered fiscal-financial backstops to keep markets operating: the EFSM (2010) and permanent ESM (2012) for sovereign liquidity, tighter fiscal-macro surveillance (Six-Pack/Two-Pack), and the start of a Banking Union (SSM/SRM) to break the sovereign–bank doom loop. The package remained partial–echoing earlier lessons from the EMS that stability mechanisms can buffer shocks yet leave periphery vulnerabilities unresolved (Höpner & Spielau 2018) – but it materially strengthened the Union’s capacity to absorb crises without reversing free movement of goods, services, and capital.

4.4. 2014 – 2024: Open Strategic Autonomy – Openness with Protective Capacity

New shocks shifted the risk locus. The pandemic triggered a fiscal leap via NextGenerationEU, pooling borrowing for recovery and for the green – digital transitions – an unprecedented move toward common stabilization (European Commission 2020). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the energy shock accelerated a turn to open strategic autonomy: staying open while managing exposure to coercion and chokepoints. In practice this meant an EU-level FDI screening regime, the Anti-Coercion Instrument (2023), and industrial policy initiatives such as the European Chips Act, alongside rapid energy diversification. Rather than protectionism, this is the geopoliticization of trade and investment policy inside an open framework (Meunier & Nicolaïdis 2019; Michaels & Sus 2024; Juncos & Vanhoonacker 2024). Historical comparison underlines both continuity and change: asymmetries that hampered coordination in 1973 reappeared in 2022, but today a thicker supranational toolkit allows for more credible collective responses (Schramm 2024).

Taken together, these developments highlight the central institutional mechanisms through which the EU sustained openness across successive crises.

Beyond the specific reforms examined in each period, several structural features of EU integration played a continuous role in reinforcing trade openness: the deepening of the Single Market reduced non-tariff barriers and ensured the free movement of goods and services; EMU and the euro lowered currency risk and stabilized cross-border transactions; the Common Commercial Policy enabled a unified external trade stance; and successive enlargements extended the reach of the acquis to new member states. Crisis-response instruments such as the ESM, Banking Union, and NextGenerationEU further strengthened the Union’s capacity to stabilize markets and limit protectionist responses during severe shocks.

The through-line is integration under pressure. From exchange-rate coordination and market-making in the 1980s, to EMU and rule export in the 1990s–2000s, to macro-financial backstops in the 2010s and today’s open-strategic-autonomy instruments, the EU has repeatedly added capacities that protect openness through turbulence. The accumulation helps explain why the Union remained a pro-globalization pole even as shocks multiplied. It also clarifies why outcomes vary across member states: incomplete fiscal union and heterogeneous energy dependencies make exposure and adjustment uneven, setting up the distributional analysis that follows.

- Results: Uneven Effects in the Periphery

Aggregate indicators show that the EU has maintained high levels of openness despite repeated crises. However, these aggregate patterns conceal substantial regional divergence, as global shocks have interacted with long-standing structural asymmetries within the Union, producing highly uneven outcomes. The distinction between Europe’s “core” and “periphery” helps to capture these dynamics: while diversified and fiscally stronger economies weathered turbulence more effectively, smaller or structurally dependent economies faced disproportionate strain (Weissenbacher 2020). Such asymmetries have also been examined extensively in Central and Eastern European scholarship, which highlights how structural legacies of the socialist period (Kornai 1992) and the subsequent trajectory of post-transition integration into Western European production networks (Csaba 2007) shaped both the opportunities and limits of openness in the region. Four vulnerabilities stand out:

– Size and diversification – smaller economies are more exposed to external demand shocks.

– Energy dependence – reliance on imported fuels magnifies vulnerability in crises.

– Global value chain position – specialization increases sensitivity to supply chain disruptions.

– Fiscal space – weaker public finances limit the capacity to cushion downturns.

These mechanisms became especially visible in Southern Europe during the eurozone crisis and in Central and Eastern Europe during the pandemic polycrisis.

| Box A: Southern Europe, 2008 – 2013.

The global financial and eurozone crises had profound consequences in Southern Europe. Greece, Spain, and Portugal experienced cumulative GDP declines of 7 – 9% between 2008 and 2013, compared with a swift rebound in Germany, which had returned to growth by 2010 (European Commission 2010; James 2014). Unemployment in the South exceeded 25%, while in core economies such as Germany and the Netherlands it remained below 8% (Eurostat 2023). Current account deficits persisted in Southern Europe, in contrast with rising surpluses in the North (IMF 2012). Export recovery lagged behind the core, constrained by competitiveness gaps and weak demand. Limited fiscal capacity forced governments into pro-cyclical austerity, deepening social distress and widening the core-periphery divide. |

| Box B: Central and Eastern Europe, 2020 – 2024.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent energy crisis exposed the structural vulnerabilities of Central and Eastern European economies. Integration into manufacturing value chains meant that the sudden halt in cross-border production in 2020 produced immediate output losses. Growth rebounded sharply in 2021, but by 2022 – 2023 this momentum faded, while core economies followed a steadier growth path (World Bank 2023). Inflation in Hungary, Poland, and the Baltic states surged above 15% in 2022, compared with an EU average of around 10% and roughly 8% in France and Germany (Eurostat 2023). High energy import dependence – over 60% of needs in many CEE countries, against an EU average closer to 40%–further eroded gains (European Commission 2022). EU-level instruments such as NextGenerationEU and coordinated energy diversification mitigated some of these pressures, but the asymmetries remained stark. |

The experiences of Southern and Eastern peripheries illustrate a recurring pattern: crises magnify structural asymmetries in the Union. While the EU as a whole maintained openness, the adjustment costs were unevenly distributed, with peripheral economies bearing heavier burdens of lost output, fiscal stress, and social dislocation. Comparative data on GDP contraction, unemployment, and inflation underline this divergence between core and periphery. Unless compensated by timely supranational instruments, integration risks reinforcing these gaps rather than narrowing them. The incremental development of solidarity tools has mitigated some pressures, but the persistence of asymmetry raises fundamental questions about the long-term legitimacy of openness in the EU.

Conclusion

Since the 1970s, the European Union has acted as a structural pillar of globalization. Despite repeated disruptions – the oil shocks of the 1970s, the global financial and eurozone crises of 2008 – 2013, and the pandemic-driven polycrisis of 2020 – 2024 – the EU consistently maintained openness. Trade as a share of GDP followed a long-run upward trajectory, with institutional innovations reinforcing integration after each crisis.

This resilience, however, came with uneven consequences. Peripheral economies, from Southern Europe during the eurozone crisis to Central and Eastern Europe during the pandemic and energy shock, bore heavier adjustment costs due to structural asymmetries in size, diversification, fiscal space, and energy dependence. The Union’s toolkit – from cohesion funds to newer instruments such as the ESM and NextGenerationEU – illustrates how institutional innovation has evolved to mitigate these imbalances.

Three lessons emerge. First, globalization advances in cycles of expansion, disruption, and recovery, rather than along a linear path. Second, resilience depends not only on open markets but also on mechanisms that fairly share adjustment costs. Third, regional integration can sustain globalization when global flows falter, but its legitimacy rests on compensating for uneven development.

Looking ahead, the EU’s history offers practical guidance. The pattern of deeper integration after each crisis suggests that Europe’s answer to volatility has been more unity, not less. This is highly relevant to current debates on “open strategic autonomy” – maintaining openness while securing critical capacities. The findings also resonate with cohesion policy discussions: if globalization’s gains remain uneven, stronger solidarity mechanisms, including potential new fiscal tools, will be essential to sustain political support for openness. In short, balancing openness with internal convergence is not just a historical challenge but a present mandate for policymakers.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the UNWE Research Programme under Research Grant No. NID NI-19/2024-A, ‘Globalization and Deglobalization: Trends, Economic Effects, and Policies’.

REFERENCES

BARBIERI, G., 2019. Regionalism, globalism and complexity: a stimulus towards global IR? Third World Thematics, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 424 – 441. ISSN: 2379-9978. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2019.1685406.

CELI, G.; GUARASCIO, D.; RELJIC, J.; SIMONAZZI, A. & ZEZZA, F., 2022. The asymmetric impact of war: Resilience, vulnerability and implications for EU policy. Intereconomics, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 141 – 147. ISSN: 1613-964X.

CERNAT, L., 2022. Has globalisation really peaked for Europe? ECIPE Policy Brief. ISSN: 1653-8994.

CSABA, L., 2007. The New Political Economy of Emerging Europe. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 9630581965.

DE GRAUWE, P., 2013. Design Failures in the Eurozone: Can they be fixed? European Economy Economic Papers, no. 491. ISSN (Internet) 1725-3187.

DINAN, D., 2014. Europe recast: A history of European Union. 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN-10. 1588262308.

DYSON, K. & FEATHERSTONE, K., 1999. The road to Maastricht: Negotiating Economic and Monetary Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN-10. 9780198296386.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. 2010. European economic forecast–Autumn 2010. Brussels: European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. 2020. Europe’s moment: Repair and prepare for the next generation. COM(2020) 456 final. Brussels: European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. 2021. Trade policy review – An open, sustainable and assertive trade policy. COM(2021) 66 final. Brussels: European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. 2022. EU Energy Dependence Indicators. Brussels: European Commission.

EUROSTAT. 2023. Unemployment and inflation statistics. Brussels: Eurostat.

FREUDLSPERGER, Ch., 2021. Failing forward in the Common Commercial Policy? Deep trade and the perennial question of EU competence. Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 1650 – 1668. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954059.

JUNCOS, A. E. & VANHOONACKER, S., 2024. The ideational power of strategic autonomy in EU security and external economic policies. Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13597.

HAMILTON, J. D., 2004. Oil prices and the macroeconomy since 1970. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 115 – 134. ISSN 0895-3309 (Print); ISSN 1944-7965 (Online).

HÖPNER, M. & SPIELAU, Al., 2018. Better than the euro? The European Monetary System (1979–1998). New Political Economy, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 160 – 173. ISSN: 1469-9923. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1370443.

IMF. 2012. World Economic Outlook: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

JAMES, H., 2014. The Euro crisis and its aftermath. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN-10. 0199993335.

KORNAI, J., 1992. The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN-10: 0691003939.

LANE, Ph. R., 2012. The European sovereign debt crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 49 – 68. ISSN 0895-3309 (Print); ISSN 1944-7965 (Online). https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.3.49.

LOOTS, El. (Ed.), 2024. Economic shocks and globalisation: Between deglobalisation and slowbalisation (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN-10: 1032607653. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003460459.

MEUNIER, S. & NICOLAÏDIS, K., 2019. The geopoliticization of European trade and investment policy. Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 57, no. S1, pp. 103 – 113. ISSN: 1468-5965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12932.

MICHAELS, Ed. & SUS, M., 2024. (Not) Coming of Age? Unpacking the European Union’s quest for strategic autonomy in security and defence. European Security, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 383 – 405. ISSN: 1746-1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2024.2376603.

MIRÓ, J., 2022. Responding to the global disorder: the EU’s quest for open strategic autonomy. Global Society, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 315 – 335. ISSN: 1360-0826. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2022.2110042.

MITTELMAN, J., 2023. Reimagining Globalization: Plausible Futures. In: M. Steger et al. (Eds). Globalization: Past, Present, Future. California: University of California Press. ISBN-10. 0520395751. https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.172.u.

NUGENT, N., 2017. The government and politics of the European Union. 8th ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN-10. 0230241182.

O’NEIL, Sh., 2022. The globalization myth: Why regions matter. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN-10. 0300248970.

ORTIZ-OSPINA, Es.; BELTEKIAN, D. & ROSER, M., 2024. Trade and globalization. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization.

OVÁDEK, M. & WILLEMYNS, I., 2019. International law of customs unions: Conceptual variety, legal ambiguity and diverse practice. European Journal of International Law, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 361 – 389. ISSN: 1464-3596. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chz041.

QUEIROZ, M. M.; IVANOV, D.; DOLGUI, A.; WAMBA, S. F., 2022. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: mapping a research agenda amid the COVID‑19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Annals of Operations Research, vol. 319, pp. 1159 – 1196. DOI: 10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7.

RODRIK, D., 2011. The globalization paradox: Democracy and the future of the world economy. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN-10. 0393341283.

SETSER, B., 2024. The surprising resilience of globalization: An examination of claims of economic fragmentation. In: M. KEARNEY & L. PARDE (Eds.). Strengthening America’s Economic Dynamism. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13973914.

SCHÄFER, Ar. & STREECK, W., 2013. Politics in the Eurozone: Integration and crisis. West European Politics, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 847 – 865. ISSN: 0140-2382. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.786650.

Fr. SCHIMMELFENNIG & Ul. SEDELMEIER (Eds.), 2005. The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN-10. 080148961X.

SCHRAMM, L., 2024. Some differences, many similarities: Comparing Europe’s responses to the 1973 oil crisis and the 2022 gas crisis. European Political Science Review, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 56 –7 1. ISSN: 1755-7739 (Print), 1755-7747 (Online). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000255.

STERN, N., 1986. Energy policy and economic growth: The impact of the 1970s oil shocks on the European economy. Energy Policy, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1 – 12. ISSN 0301-4215 (print); 1873-6777 (web).

STIGLITZ, J. E., 2002. Globalization and its discontents. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN-10: 0393051242.

WEISSENBACHER, R., 2020. The Core-Periphery Divide in the European Union: A Dependency Perspective. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783030282103.

WOLF, S.; TEITGE, J.; MIELKE, J.; SCHÜTZE, F. & JAEGER, C., 2021. The European Green Deal – More than climate neutrality. Intereconomics, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 99 – 107. ISSN: 1613-964X.

WORLD BANK. 2023. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

YERGIN, D., 1991. The prize: The epic quest for oil, money, and power. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-50248-4.

Dr. Paskal Zhelev, Assoc. Prof.

WoS Researcher ID: C-1732-2019

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-0722-7588

University of National and World Economy

1700 Sofia, Bulgaria

Bratislava University of Economics and Business (EUBA)

Dolnozemská cesta 1, office+: D 430

852 35 Bratislava, Slovakia

E-mail: pzhelev@unwe.bg

Dr. Monika Moraliyska, Assoc. Prof.

WoS Researcher ID: AAG-8613-2021

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6199-9458

Dr. Ivet Tileva, Chief Assist. Prof.

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7726-1258

University of National and World Economy

1700 Sofia, Bulgaria

E-mail: mmoraliyska@unwe.bg

E-mail: itileva@unwe.bg

>> Изтеглете статията в PDF <<