Georgi Kostov

Agricultural University – Plovdiv

https://doi.org/10.53656/voc25-3-4-03

Abstract. In recent years, there has been an increasing discussion about „green“ economy in vocational education. Climate change, the influence of environmental factors, problems, related to food quality and nutrition of the population, as well as economic and political problems on a global scale are the main reasons for the need for „green“ education starting from vocational high schools of agriculture. The „green“ skills are in high demand as many jobs increasingly require these competencies, and these skills are essential for preserving or restoring the environment, as well as for „greening“ or „greenifying“ the existing jobs. The article presents the essence of green skills, describes their conceptual framework and develops methods and pedagogical approaches for the successful formation of green skills in vocational education in agricultural disciplines.

Keywords: „green“ economy, „green“ education, „green“ skills, vocational education, agricultural disciplines

- Introduction

Over the past decade, a key goal of education around the world has been to teach students, both in school and in universities, to understand for themselves how the world actually works and how important green education is. The process of „greening“ the economy and the education is a shared goal for both advanced and less advanced economies alike, particularly where sustained and inclusive employment is an objective for policy-makers. Its growing popularity is largely due to the numerous crises that the world has faced in the recent years – mostly climate changes, wars, hunger, financial and economic. Green skills are considered a key precondition for sustainability transitions (Fuchs, 2024, 1; UNESCO 2022; UNESCO & UNEVOC 2017; UNIDO 2022).

In various countries and regions, environmental and educational policies exist which promote the implementation of green skills in vocational education and further training (CEDEFOP 2023; Fuchs, 2024, 1; Vona et al., 2018). They can be defined as the knowledge, abilities, values and attitudes needed to live in, develop and support a society which reduces the impact of human activity on the environment. Green skills are often associated with sectors that will play a major role in reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, such as power, home heating, waste and resources.1 Green skills describe the knowledge that we all need to develop and live in a sustainable society and environment.2

Green skills have to prepare the children for their future careers. Regardless of whether they continue their professional path in the field of agricultural sciences or not, the issue of the state of the environment concerns every person on the planet. As the climate crisis continues, the humanity needs more and more people with expertise in sustainable development and the environment in every single industry.

- 2. Conceptual framework of the green skills

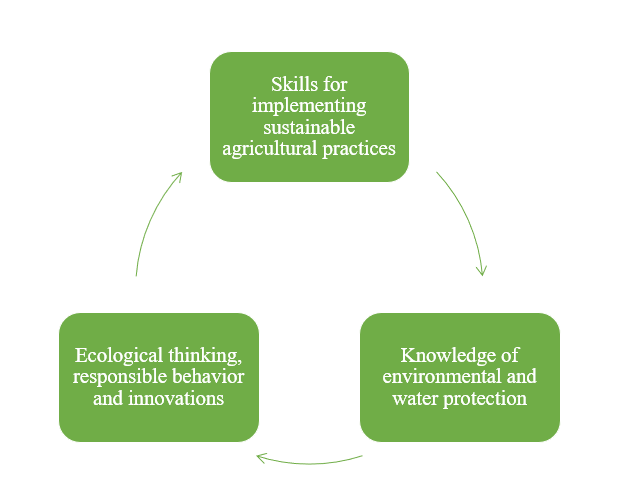

According to the Unted Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change green skills are „technical knowledge, expertise and abilities that enable the effective use of green technologies and processes in professional settings.“ There are grand expectations that the green skills will enable and motivate the learners (apprentices and students, employees and entrepreneurs) to lessen the environmental impact of their work. They are considered to enhance resource efficiency and promote biodiversity, mitigate global warming, reduce the carbon footprint and lower environmental pollution and degradation. As a complex set of competencies (Fig. 1), they enable individuals to work in an environmentally sustainable, economically efficient and socially responsible manner.

Figure 1. The green skills as a complex set of competencies

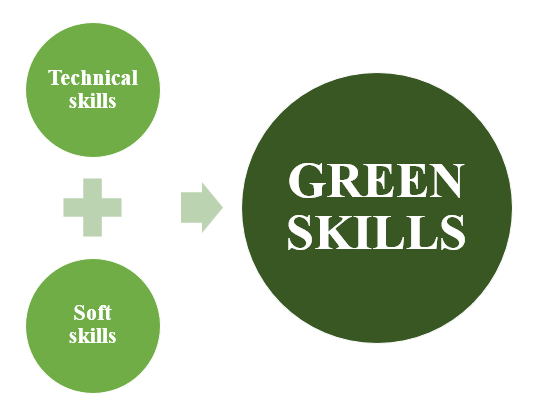

In addition, green skills are expected to contribute to ‘just transitions’, particularly aiming at the reduction of regional disparities, social inequality and poverty. Green skills shall improve working conditions, and promote participation, co-determination and empowerment (Auktor, 2020; Fuchs, 2024, 1; Gallehr et al., 2009; Vona et al., 2015). By their nature, green skills can be sub-categorized into two main groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the green skills

The technical skills are the skills needed for implementing, developing and/or maintaining green technologies and infrastructure. For example, knowledge of renewable energy technologies, drones and water resource management, installation and operation of solar panels, etc. The soft skills are social, transitive skills related to human abilities to work with other people. They involve critical and strategic thinking, teamwork, making sustainable decisions, civic responsibility towards the environment.

Once acquired, social skills can be „transferred“ to any situation, organization or team in which the individual decides to work, entertain or live (Velikova & Kamenova, 2019, 214).

- 3. Formation of green skills in vocational education: methods and pedagogical approaches

The formation of green skills requires the implementation of targeted and innovative learning methods that go beyond and improve the traditional form of teaching. These methods and approaches should encourage students’ active participation in real-world situations, critical thinking, independence, responsibility and interdisciplinarity.

Problem-based learning (PBL). Problem-based learning emerged as the result of an attempt to reform medical education at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, in the late 1960s (Schmidt 2012, p. 22). Problem-based learning starts with a problem (case) that drives the learning process and is active, collaborative, integrated, and oriented to the way adults learn (Jones, 2006; Prasad & O’Malley, 2022, 52). A typical PBL group usually consists of 6-8 students (sometimes 9) predetermined by the teacher. The case is delivered through sequential disclosure, in the span of typically three sessions, with small increments of the case being delivered one at a time after the previous part has been discussed. According to Jones (2006) this allows students using information revealed in the case parts to apply and use it for appropriate discussions.

The discussions must include differential diagnoses and formulation of questions that need to be explored (Prasad & O’Malley, 2022, 53; Ricanati, 2014). As students work at their own pace through each case, an environment of student-driven learning is created and they solve the case problems as a group. At the conclusion of the session, the group develops a set of learning objectives (LOs) to help them better understand the basic science and other components of the case (Prasad & O’Malley, 2022, 53; Ricanati, 2014). These objectives are later divided among each group member for individual presentations in the following session. For example, students can be engaged in solving case studies such as (1) how to reduce pesticide use or (2) how to improve soil fertility through the use of pure organic matter.

Project-based learning. Its learning is organized around projects. Project-based learning is an approach extremely well suited to achieve more contextual, durable outcomes for students that study agricultural disciplines. Fincher & Knox (2013) describe it as „students in sustained, collaborative focus on a specific project, often organized around a driving question.“ These aspects are critical: sustained collaboration over a deep interaction requires learners to establish a rhythm and working process to solve a complex problem (Gary, 2015, 99).

Project-Based Learning is a student-centered approach to teaching where students engage in real-world projects to learn and apply their knowledge and skills. Instead of memorizing information only, students actively work on projects, often in groups, to solve problems, exchange ideas, investigate questions or create products. This method aims to foster critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving abilities. Project-based learning involves developing and implementing specific initiatives with an environmental focus. For example, students can work on building a school organic garden, monitoring water and soil quality and plant health, and conducting various composting and biofertilization campaigns.

Field-based learning (FBL). Conducting practices outside the classroom (on farms, research stations, institutes, farms) contributes to a better and more comprehensive understanding of ecological processes and problems. Field trips can be defined as “any journey taken under the auspices of the school for educational purposes” (Fedesco, Cavin & Henares, 2020, 66; Sorrentino & Bell, 1970, 223). Much of the research on field trips agree that the intended educational outcomes of field trips focus on the following six areas: developing green skills; developing social and personal skills; adding relevance and meaning to learning; developing observation and perception skills; providing first-hand real-world experiences; enhancing interest in the subject and intrinsic motivation.

Field-based learning for students can include visits to organic farms, meetings with various scientists and specialists in the field of agriculture and working with farmers applying sustainable methods.

Use of digital tools and simulations. In the modern world, information technology, digital technologies and artificial intelligence are completely commonplace. They have been successfully implemented and used in agriculture, science, medicine etc., as well as in education. Simulators and virtual laboratories can be successfully used to develop green skills among students, for example 3D simulations of ecological systems, virtual cultivation of different groups of crops (cereals, legumes, industrial crops, forage crops) with given variable parameters (climate, soil type, fertilization etc.). The implementation of agro-digital technologies such as drones, sensors, various types of agro-management software (fertilization, irrigation, soil cultivation planning), use of geographic information systems (GIS) can also show extremely good results among students.

- Conclusion

The green skills are a key factor for the future of sustainable agriculture. The future of agricultural education lies in students’ interaction with nature, in being closer to farmers and scientists. The first step for this is the successful preparation of students in vocational high schools of agriculture. Vocational agricultural education should not only meet the great needs of the market, but also prepare personnel, that is capable of thinking and acting sensibly and responsibly towards the environment. Integrating green competencies into educational programs would be a successful investment for the better future of the world and society.

NOTES

- West of England Mayoral Combined Authority. Green skills. Retrieved from: www.westofengland-ca.gov.uk.

- UNICEF (2024). What are green skills? Retrieved from: www.unicef.org.

REFERENCES

Duisenbaeva, S. T. & Baisalbaeva, R. A. (2019). New aspects of the formation of „green skills“ in the sphere of education in higher education institutions. Mechanics and technology, 63(1), 210 – 217. ISSN 2308-9865.

Fedesco, H. N.; Cavin, D.; Henares, R. (2020). Field-based Learning in Higher Education: Exploring the Benefits and Possibilities. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 20(1), 65 – 84. ISSN 1527-9316.

Fuchs, M. (2024). Green Skills for Sustainability Transitions. Geography Compass, 18(10), 1 – 12. ISSN 1749-8198.

Gary, K., 2015. Project-Based Learning. Computer, 48(9), 98 – 100. ISSN 0018-9162.

Prasad, S. & O’Malley, C. (2022). An Introductory Framework of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) and Perspectives on Enhancing Facilitation Approaches. HAPS Educator, 26(3), 52 – 58. ISSN 2473-3806.

Schmidt, H. G. (2012). A Brief History of Problem-based Learning. In: O’Grady, G.; Yew, E.; Goh, K.; Schmidt, H. (Eds.). One-Day, One-Problem, 21 – 40. ISBN 978-981-4021-75-3. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 978-981-4021-75-3. Available from: Springer Nature Link.

Velikova, V. & Kamenova, D. (2019). The Status of Social Skills Among Students from Croatia and Bulgaria. In: Radev, T.; Arhipova, S.; Kamenova, D.; Yordanova, S. (Eds.). Yearbook of Varna University of Management Volume XII, 214 – 231. ISSN 2367-7368. Varna: Publishing house of Varna University of Management.

Georgi Kostov

ORCID iD: 0009-0004-1269-6604

WoS Researcher ID: KIE-6155-2024

Agricultural University

Plovdiv, Bulgaria

E-mail: georgikostov@au-plovdiv.bg

>> Изтеглете статията в PDF <<